Andrey Popov (Shutterstock)

Is AD diagnosis shifting?

The current status quo for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis relies heavily on the onset of cognitive decline. By that stage, the proteopathies (disease-causing misfolding proteins in the brain) have likely spread notably. This delays intervention, reducing the likelihood of effective symptom management or lifespan extension. While the advent of PET scans–using radiotracers to measure the harmful protein concentrations in the brain directly–enabled the reliable diagnosis of degenerative conditions like AD, they are expensive, relatively inaccessible, and expose the individual to some radiation. After that, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) markers that are pervasive today have become viable biomarkers for indirect measurement of proteins like phosphorylated tau variants (p-tau217, p-tau181, etc.) to then be attributed to AD pathology. CSF extractions, however, require lumbar punctures that are invasive and painful for the patients and require special expertise (infringing on the scalability of this tool as a result). Now, highly accurate blood test-derived biomarkers are on the rise with great promise in terms of accuracy (to attribute to AD pathology), scalability and cost-effectiveness, and accessibility to communities wherein pricy, cutting-edge neuroimaging technologies like PET are inconceivable.

PET Brain Scan (2021)

Just a blood draw?

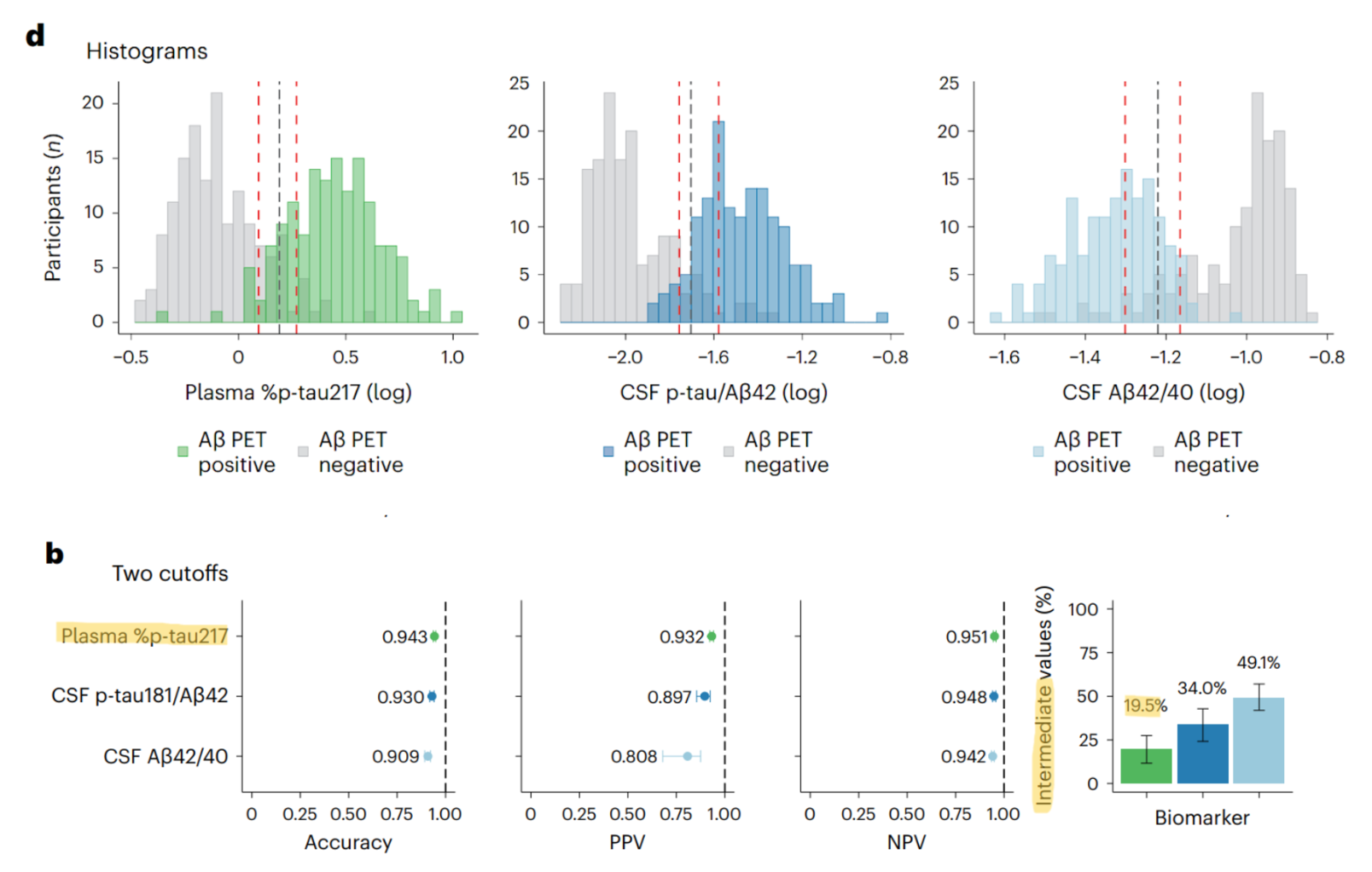

Barthélemy et al. (2024) demonstrated their blood test’s accuracy (focused on the p-tau217 biomarker) to be comparable and/or better than existent CSF markers (specifically the AB42:40 ratio and the p-tau181:AB42 ratio). The accuracy of all three were vetted against the gold standard biomarker in this diagnostic niche, PET scans (PET scans are considered the gold standard because of their direct measurement of proteopathy spread and spatial monitoring of it to the indirect measurement of p-tau in the CSF or blood). Findings from Leuzy et al. (2022) support the choice to focus on p-tau217 as the most compelling blood-based biomarker considering its higher predictive value of AD progression (MCI and early-stage dementia groups) to other p-tau variants and optimal prediction of AD onset in conjunction with tau PET imaging. With that, they also claim that p-tau217 is consistent and higher in AD than in other neurodegenerative diseases, potentially making it valuable as a distinct biomarker to delineate between different types of these conditions in the diagnosis stage.

How accurate and reliable is this?

It’s worth noting that the authors’ choice to use the p-tau:unphosphorylated tau ratio rather than just report the magnitude of p-tau217 changes in participants is pertinent to distinguishing AD from other conditions that can increase p-tau systematically (like chronic kidney disease). Mutations to the MAPT gene (that codes for the tau protein) can cause abnormal phosphorylation–like p-tau217–leading to neurofibrillary tangles implicated in AD for eliciting neurodegeneration of brain cells. Relatedly, other mechanisms like neurodegeneration of cells (due to such proteopathies) in AD cause tau instability leading to the accumulation of the unphosphorylated form. Considering, both the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of tau increase in parallel in AD, hence the apt choice to report the ratio to correct for the possible influence of other diseases. Further into the technical strengths of these researchers’ work, they reported the intermediate group (after bootstrapping their data, the number of data points within their two thresholds for sensitivity and specificity of the data; ie. where the true positive and true negative curves overlap…and where most false positives and false negatives lie) for their blood test results which demonstrated lower levels in this region to the existent two CSF markers compared against. While this is compelling in terms of the technical robustness and future of biomarker work for AD, there are ethical and social implications to consider.

What does this mean for us?

The inclusion of different demographic groups, for example, is an imperative next step in this research. Nuance in individual differences must be captured to best personalize treatments to people with differing physiological profiles. For instance, Dotson & Duarte (2019) documented that baseline white matter hyperintensity volume is more predictive of cognitive decline in Hispanic-American groups to global grey matter change for the Caucasian/African-American groups. Personalized diagnostic approaches based on subgroups must be considered to avoid perpetuating health inequities with the emergence of new health technologies.

Ethically, it is important to consider the potential mental anguish and personal damage that could arise from screening for biomarkers like p-tau217 (with predictive value for AD pathology), especially given the absence of a retroactive treatment for AD. This is important to consider alongside the notion that information is power and that awareness of the possibility enables financial/care planning for the future, lifestyle changes to subside the onset and severity of symptoms, screening family members for related genetic risks, etc.

I have so many questions…

The status quo is evidently evolving as we unveil more about AD progression, modulation, and potential intervention. However, considering the necessity to triangulate data regardless of how accurate the biomarker blood test is (when people’s lives are at stake, practitioners must ensure surety before making a misdiagnosis that costs the patient’s psychological well-being) and the above ethical debate, I’m reminded of the quote ascribed to humankind’s greatest thinkers like Socrates and Einstein: "The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don't know."

References

Barthélemy, N. R., Salvadó, G., Schindler, S. E., He, Y., Janelidze, S., Collij, L. E., Saef, B., Henson, R. L., Chen, C. D., Gordon, B. A., Li, Y., La Joie, R., Benzinger, T. L., Morris, J. C., Mattsson-Carlgren, N., Palmqvist, S., Ossenkoppele, R., Rabinovici, G. D., Stomrud, E., … Hansson, O. (2024). Highly accurate blood test for alzheimer’s disease is similar or superior to clinical cerebrospinal fluid tests. Nature Medicine, 30(4), 1085–1095. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02869-z

Dotson, V. M., & Duarte, A. (2019). The importance of diversity in Cognitive Neuroscience. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1464(1), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14268

Leuzy, A., Smith, R., Cullen, N. C., Strandberg, O., Vogel, J. W., Binette, A. P., Borroni, E., Janelidze, S., Ohlsson, T., Jögi, J., Ossenkoppele, R., Palmqvist, S., Mattsson-Carlgren, N., Klein, G., Stomrud, E., & Hansson, O. (2022). Biomarker-based prediction of longitudinal tau positron emission tomography in alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurology, 79(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.4654